The Dominican Republic is where you’ll find the Caribbean’s highest peak, Pico Duarte, measuring 3175 metres. Mile upon mile of white sand lines its coastline, a fact that hasn’t gone unnoticed by the holidaymakers who fly there to flop beneath its shady palms. Windsurfers and whale watchers won’t come away disappointed. But there’s far more to the Dominican Republic than its beaches.

The influence of the Spanish

For years, many a school textbook claimed that Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas, setting foot on what he would later be named the island of Hispaniola in December 1492. In 1493 Christopher Columbus came back, this time to the north coast. He founded La Isabelica, close to Puerto Plata, though the settlement would be short lived. Not so down south: in that part of the Dominican Republic New World firsts come in batches: the first university, the first hospital, the first customs house and the first paved road in the Americas were all here.

Christopher Columbus’ younger brother Bartholomew founded Santo Domingo a few years later. There, the Catholic faithful erected the first cathedral and built mansions worthy of their elevated status. For over three centuries, the place would be known as the Spanish Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, until in 1821 came a declaration of independence. Yes, the Dominican Republic was once known by the name of its present day capital city.

How Santo Domingo has changed

That city has moved once – from its original site on the east bank of the Ozama River to the west. It’s also changed its name. During the rule of Rafael Trujillo it briefly became Ciudad Trujillo, opting to revert to Santo Domingo when the dictator was assassinated in 1961. And of course it’s grown, massively in fact. These days, the city is the largest by population not only in the country, but also in the Caribbean, home to over 3.5 million people.

Discover the Zona Colonial in Santo Domingo, the nation’s capital

Today, the centre of Santo Domingo is still referred to as the Zona Colonial and has been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list since 1990. It’s where you’ll find the greatest concentration of 16th century buildings, many of which have been repurposed.

Calle de las Damas was built in 1502, making it the oldest paved street in the Americas, though back then they called it by a different name: Calle de la Fortaleza. The fort which gave the street its name is now over 400 years old. Fortaleza Ozama has served as a military base for almost its entire life, opening to tourists as a visitor attraction in the 1970s.

Like most surviving structures from that era, African and Taíno slaves built it. Partially constructed from coral stones, it was originally intended to guard the city from possible attack from the sea, though ironically the walls that front onto the river are thinner than those on the landward side.

The legacy of the conquistadors

A little further down the street, on the corner with El Conde, is another building that Governor Nicolás de Ovando ordered to be built. These days, it’s known as Casa de Francia as it houses the French Embassy. The house would have many tenants, among them some of the conquistadores who stayed to plan their expeditions. Hernán Cortés, who would go on to conquer Mexico, and Francisco Pizarro, who would trick Atahualpa and cause the fall of the Inca Empire in Peru, are two of the most famous.

In 1509, Christopher Columbus’ son came to settle in Santo Domingo, succeeding Nicolás de Ovando as governor and later becoming viceroy. His wife was Maria de Toledo, the niece of King Ferdinand of Spain. As befitted royalty, there was also an entourage. The habit that the ladies had of strolling along the street to go to mass or simply to chat led the street to be named Calle de las Damas. Diego and Maria occupied the Alcázar de Colón, which is now a museum housing many of their personal possessions.

The fate of the first monastery of the New World

The first monastery of the New World, a few blocks to the west, hasn’t stood the test of time quite so well. The Monasterio de San Francisco is now a partial ruin, though enough remains of the original structure for your mind to be able to fill in the gaps. A group of Franciscan monks established it in 1508, but disaster struck in 1586 when Sir Francis Drake (brave explorer or ruthless pirate depending on your point of view) set it on fire.

It was rebuilt twice, only to be destroyed by earthquakes in 1673 and 1751. By the end of the 19th century it had been turned into an asylum for the insane. A powerful Category 4 hurricane which blew through in 1930 finished it off for good, leaving a trail of devastation in its wake which would leave thousands of people dead. Today, the ruins stand as a monument to its unfortunate past.

An island steeped in history

But the history of the Dominican Republic extends back far beyond the arrival of Columbus. The indigenous Taínos, whose name translates as “friendly people”, populated the island and others nearby. They lived a subsistence lifestyle, growing crops such as sweet potatoes, maize, yuca (cassava), pineapples, tobacco and peanuts. Today, in the countryside, some of those traditional practices survive to a certain extent.

When the Spaniards arrived, they were predominantly male; Taíno women were taken as common-law wives and many bore mestizo children. In need of forced labour, the Spanish put males to work in gold mines such as Pueblo Viejo and on plantations.

The Taíno tragedy

The Taínos experienced food shortages and worse, had no immunity to diseases carried by the Europeans, such as measles and smallpox. 90% of a population numbering hundreds of thousands succumbed to smallpox in the 1518 epidemic. 30 years later, there were fewer than 500 left and soon they were wiped out completely. Unlike the architectural legacy left by the Spanish conquistadors, little tangible evidence remains of Taíno civilisation. They lived simply in communal dwellings made from mud, straw and palm leaves, sleeping in cotton hammocks or on mats on the floor.

The contribution of the Taínos to Caribbean culture

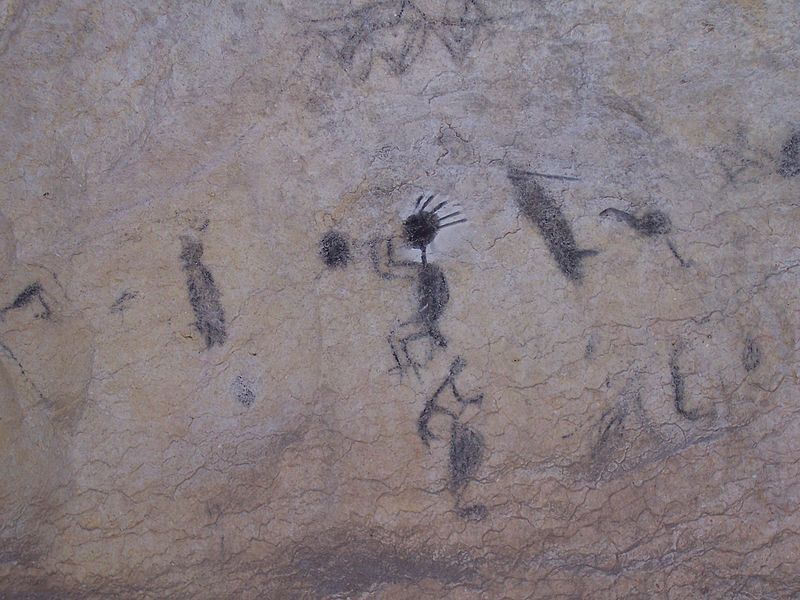

Travel an hour or so from Santo Domingo, however, and you’ll reach the Pomier Cave system. They contain the largest collection of Taíno rock art in the Caribbean. For centuries before the arrival of Columbus, the Taíno shamans set out for the caves to seek enlightenment as to what the future would hold and to pray for rain to water their farmers’ crops. They would draw images on the walls of the caves: dogs, birds, turtles, fish. Each creature symbolised a different aspect of their life, fertility, healing and death, for starters.

In one cave, a carved image of a face peers from the stone. The figure is Mácocael, a figure whose job it would have been to stand guard. The temptation to leave his post and seek the sun, so legend has it, had devastating consequences, and he was turned to stone. In the Taíno language, his name means “No eyelids”.

Back in Santo Domingo, the Museo de las Casas Reales traces the history of the Dominican Republic from Taíno times to the present day, warts and all. It’s a must for visitors who want a reminder that Columbus didn’t discover the Americas at all: communities such as those of the Taíno people were already thriving long before he showed up.